THE TECHNIQUE OF CRITICISM IN EDVARD MUNCH

By Chaim Koppelman

from Four Essays on the Art of the Print

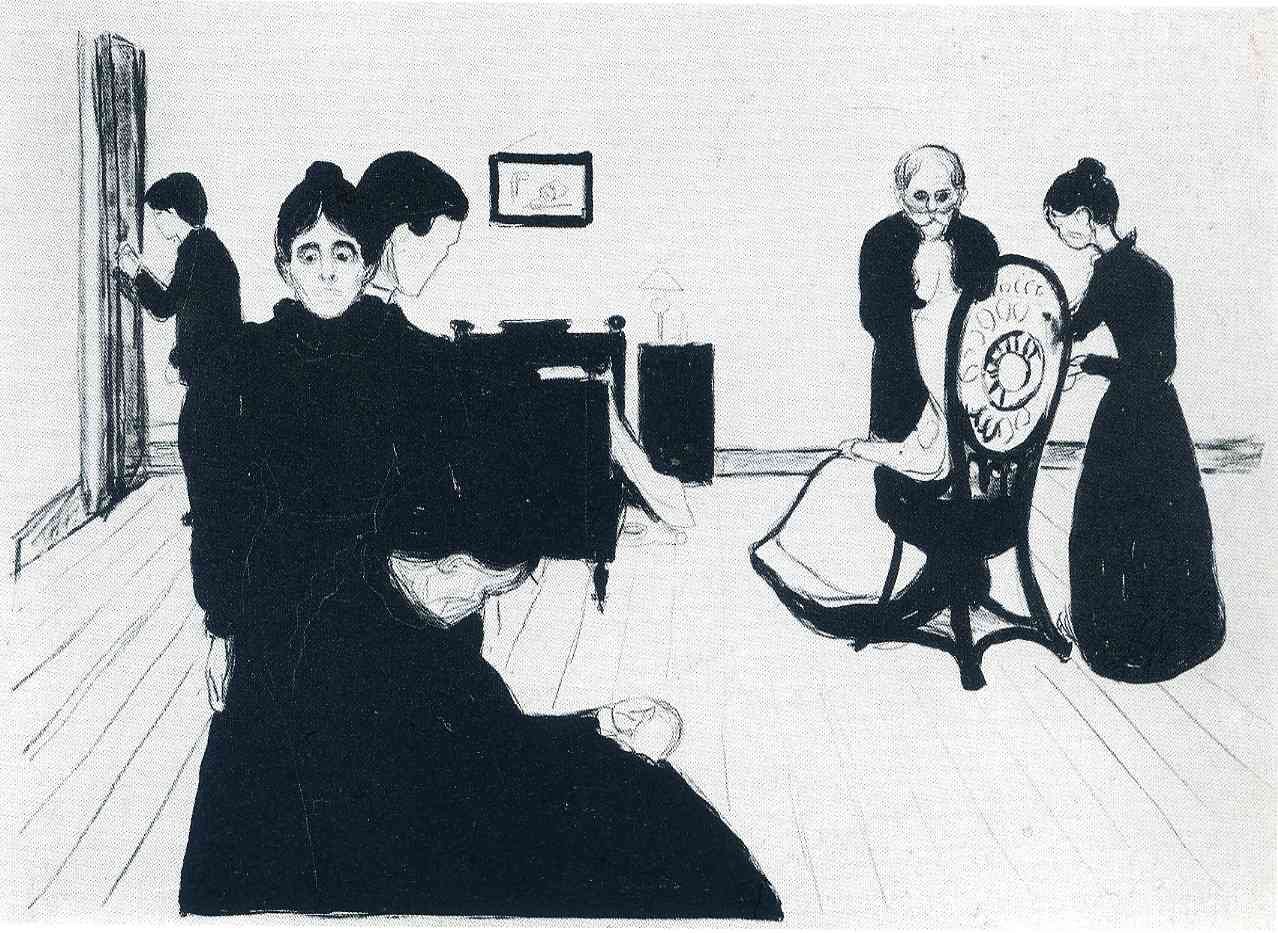

Death Chamber, 1896. Lithograph

I have been tremendously affected looking freshly at work I have loved for many years, the powerful prints of Edvard Munch, and seeing more of the artist’s intention through this great Aesthetic Realism principle stated by Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

I have come to see a new relation between Munch’s earliest lithographs (1896), Anxiety and Death Chamber. They are both beautiful because the artist is courageously dealing with and showing a dramatic oneness of closeness and distance, presence and absence—the same opposites the Norwegian artist saw fighting and causing so much pain, not only at a time of death but every day in people’s lives, including his own.

The purpose of art and the purpose of life, I learned from Aesthetic Realism, is exactly the same: to like the world through knowing it, seeing it as an aesthetic structure of opposites. Like his contemporaries and friends, Ibsen and Strindberg, Munch was a critical observer of individuals, couples, the family, crowds. His art is for life because he shows the vivid and composing presence of reality’s opposites even when people seem most troubled and most separate or isolated.

In A Rosary of Evil, Eli Siegel wrote:

Evil [is] not having the principle of closeness and separation as one thing…. Good is a sufficient junction of the ideas of junction and separation. That makes it like art.1

Munch’s Death Chamber is a critical work about separation and junction at a time of actual death, and like other prints, it is based on what the artist remembered of his mother’s and later his older sister’s death, with the mourning family present. Anxiety, however, is about an insidious, everyday death which Munch also observed and described: “I see behind everyone’s masks. Peacefully smiling faces, pale corpses who endlessly wend their way down the road that leads to the grave.”2

Contempt Is Against Life

What the artist saw is the terrible effect of unjust contempt, which is described by Aesthetic Realism as the beginning cause of human evil: “There is a disposition in every person to think he will be for himself by making less of the outside world.” And, in his “Poetic Notes on Contempt” Eli Siegel stated: “...contempt, however subtly and however overtly...is against life.”3

Munch’s prints often show people literally taking the life out of each other — using their closeness to one another to be contemptuous, oblivious to the outside world. When we want to find the world dull and meaningless, not worthy of interest, we become blank and empty ourselves. This is the very antithesis of the art way of seeing.

Anxiety is a later form of Munch’s painting Spring Evening on Karl Johan Street, described by Peter Guenther as a procession of “hollow-faced, blank-faced people...isolated from each other, lonely, troubled and uncommunicative...as in a dream, oblivious of their surroundings.” 4

I believe that in the print the artist wanted the four figures in the foreground to be felt as more closely related. In the painting a family relation among the foreground figures is only hinted at. In the print they clearly form a unit, distinctly felt as apart from the more anonymous crowd behind them. This idea is furthered by their similar size, expression, shape, and distance from one another, resulting in an enclosed movement as our eye moves around from one face to the other. And Guenther makes another crucial comparison:

Munch did not put this group of people on Karl Johan Street as in the painting, but used the Oslo fjord as a background; he in that way widened his view. Anxiety is not only a city phenomenon but a general human condition. 5

In changing the setting Munch heightens the dramatic tension between separation and junction, of the four people as close and in relation to the whole world. Both conceptual changes result in a work of greatly increased power, concision, depth and beauty.

Anxiety, 1896. Lithograph

The print is entirely in black and white except for red stripes curving horizontally across the sky. Man and woman, young and old, share a common, chalky pallor. No figure has its own complete outline, its individual shape. There is a frightening insistence on separation within junction, alienation within the huddle.

Two Forms of Contempt: To Discard and to Own

In the Aesthetic Realism classes I attended, Eli Siegel criticized and changed the way I saw the world, and what I learned about art and my own work has enabled me to better understand Munch’s intention here. Mr. Siegel described two forms of contempt: “There’s a triumph in being able to forget those one is close to, and a triumph in saying ‘They’re mine....’ To be in a state where you want to discard and also own is to be in a state of dichotomous frenzy.”

Edvard Munch’s lithograph powerfully pictures and criticizes that “dichotomous frenzy.” The red stripes enliven and also warn: evil is going on here, take care! Munch’s sky won’t let these people triumphantly “discard and also own” one another. Stripes are insistently repeated in the landscape and get into the children’s hair. The rhythmic lines in the background join the curving outlines of the black mass. There is a thrilling simultaneity of near and far, junction and separation. That big top hat in the center has both a formal and critical function—and a touch of satire. It joins people, land, water and sky. And doesn’t its jolly, forward tilt counter the symmetrical grimness of those four faces confronting us? Munch, as artist and critic, shows how in reality, the family is both separate and related.

Absence in Closeness, Near and Far

Anxiety is a marvelously rich mingling of terror and beauty. As this procession of humanity approaches, their expressions become increasingly vacant and remote until those closest to us look miles away. Munch’s technique makes absence in closeness palpably present.

Aesthetic Realism teaches people how to see the world, art and oneself as a structure of opposites—sameness and difference, the near and far, order and disorder, and more. This knowledge is what Edvard Munch yearned for when he wrote about his art: “I shall not give up hoping that with its assistance I shall be able to help others achieve their own clarity.”6

Mr. Siegel said in the class I quoted from earlier:

People in a family should see each other as near and far at once. If a member of the family said: ‘I belong to you, family, I am of you; but I am also of the whole universe, I am of everything’—that would make sense.

When Eli Siegel showed that what makes a work of art beautiful—the oneness of opposites—is the same as what every individual and member of a family wants, it was one of the mightiest and kindest achievements of man’s mind.

REFERENCES:

1. Eli Siegel, A Rosary of Evil (New York: Terrain Gallery, 1964).

2. Frederick Deknatel, Edvard Munch (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1950).

3. Eli Siegel, “Poetic Notes on Contempt,” The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, #839 (1989).

4. Peter Guenther, Exhibition catalogue, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Gallery, University of Houston, 1976.

5. Ibid.

6. Deknatel, op. cit.